There are many stunning shots in Andrea Arnold’s adaptation of Wuthering Heights. The finest feature Cathy as a young woman wandering amongst the moors, isolated and completive. Often, she is framed by the elements; the wind batters her, blowing her hair loose around her face as she sits thoughtful on a jagged rock. In other shots, the trees seem to curl into archways as she hovers at the edge of a glade lit by dusty sunlight or the mist clings to her blood red petticoat as she marches across the brutal landscape. Just like in the novel, Cathy’s being is represented by the wilderness around her. She is dark, brooding, and, at times, cruel yet she has the capacity for beauty in the form of a deep, obsessive love for Heathcliff. For all its imperfections, Arnold’s film captures this aspect of the novel most succinctly in these sparse shots. The outer world reflects the inner one in a way that feels deeply novelistic. Even if other films capture the book’s narrative better—that is to say, however, that no film to date has adequately done the novel justice—when I think of Cathy Earnshaw I think of Arnold’s interpretation; a woman walking free in the wilderness.

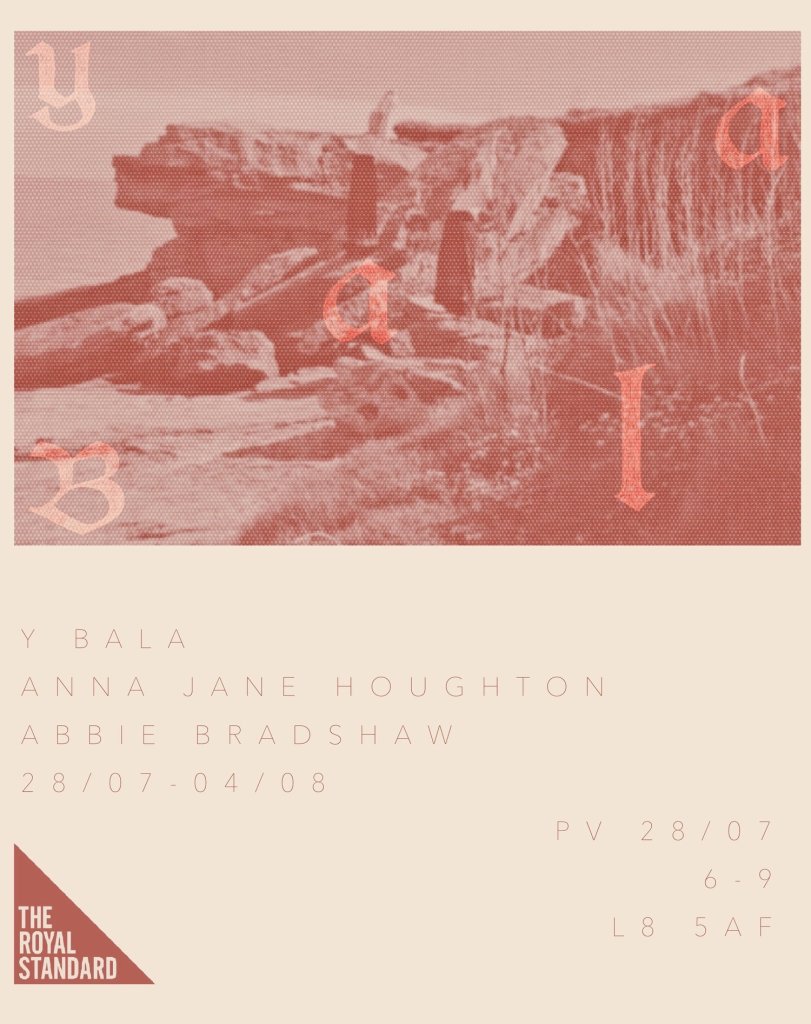

Cathy on the moors is not the only example of the connection between a woman and the wild. In almost all ancient myths, women are connected to the earth as the figure of Mother Nature recurs in different forms; Gaia in the Greek, Nokomis to the Indigenous Peoples of America, Mama Pacha to the Incas, and so on. This has meant, historically, nature has often been viewed as feminine. As such, for artists and writers to envision women in nature is to imagine a connection to femininity as they perceive it. We see it in the recently rediscovered turn of the century photographs of Anne Brigman whose nude models lounge and bathe in California’s Sierra Nevada Mountain range. It’s present in the relationship between Mary Oliver and the natural subjects of her poems, in the animals and flowers she depicts. It is evident in the land-based works of Ana Mendieta such as her Volcano Series in which the Earth’s representation as a woman and mother is directly addressed. It’s apparent in the images from Y Bala, too, as the artists embrace nature both figuratively and literally.

Yet, to be one with nature and to be wild are different things. The former is about being comfortable with the outdoors, finding peace amongst the flora and fauna, but the latter suggests a separation from something tamed, from something docile or domestic. This is a concept the above artists understand. Wildness is behavioural. It is connected to our inner most desires, our sexuality, our temptations, and our intuition. To be wild is to be unrestrained, to engage in acts that don’t conform to socially accepted ways of being. As Jack Halberstam has it ‘Wildness names simultaneously a chaotic force of nature, the outside categorization of unrestrained forms of embodiment, the refusal to submit to social regulation, loss of control, the unpredictable.’ It’s no surprise, then, if wildness is connected to a kind of social chaos, that to be called ‘wild’ is often derogatory. To be a wild woman is to be a problem that needs to be solved. So much so that in her 1992 book, Women Who Run with the Wolves, Clarissa Pinkola Estés posits that the ‘Wild Woman’ is an ‘endangered species.’

The endangered Wild Woman conjures up images of women disappearing, dying out, and becoming extinct which, once again, connects women to the natural world and to the many animal species that have gone the same way. How it happens in both cases is similar; they are stamped out or eradicated. In Wuthering Heights, Cathy’s wildness is squeezed out of her when she is forced to stay with a wealthy family as she recovers from an injury. Upon returning home, she is ‘dignified’ and sails gracefully into rooms. Cathy is not alone, either. The titular Shrew is tamed in Shakespeare’s play, Eliza Doolittle ends Pygmalion a well-to-do woman. Each horror movie’s moral ruling tells us only the virginal, strait-laced Final Girl can live, meaning that all the wild women are slain by the time the credits roll. These are all examples of women who are pulled from their wildness. However, if these women aren’t saved from it by a man or by their status as morally virtuous, then they are lost to the wildness. The once beautiful Medusa, for example, is raped by Poseidon and is punished for the act by Athena who turns her into a monster. Soon Medusa’s head is sliced from her body and used as a weapon by Perseus at once killing the beast and weaponizing her power. The teenager at the centre of the 1976 film Carrie dies after she finally unleashes her wild side. Brontë’s Cathy, in sickness, is drawn back to Heathcliff and flirts with wildness again. As such, she dies too.

Often, these stories are about assimilating a wild woman into or removing her from society as a means of strengthening its moral fabric. Not only that, but we understand that if these women remain untamed then they must be punished. Ultimately, these ideas exist far beyond the confines of myth and narrative. Contemporary wannabe lotharios and pseudo-philosophers discuss the topic regularly on their podcasts, expressing their desire to own subservient women. As such, a woman’s role as a sexual object and secondary citizen is extolled to teens all over the internet. This facilitates theories about the ‘matrix’ and ideas about women who, in their language, constitute sluts, ‘feminazis’, and woke ‘libtards’ who need to get laid.

Yet, this behaviour can’t exist in a vacuum. Rather, the culture at large seems determined to eradicate wildness. In the USA and UK, there is a push toward a religious puritanism that seeks to condemn sexuality, gender fuckary, expression, and art. Laws in both countries are intent on forcing women into the position of simply being a body with no autonomy and this is particularly true of Trans women who attract the most ire. While we can’t assume the category of ‘Trans women’ to be a homogonous group, we can see that their sense of being relates to Halberstam’s ideas on wildness as Trans women and nonbinary people pose the most serious threat to ‘social norms’ through their ‘refusal to submit to social regulation’ that would see them confined to the gender they were assigned at birth. Thus, they are the focal point of current attacks. As Rebecca Solnit wrote in The Guardian in 2020:

Patriarchy would like gender to be fixed and a lot of its violence is punishment of women who aren’t submissive enough, men who aren’t straight enough, and anyone else who steps out of line.

How this ‘fixing’ of gender works is through a co-opting of nature and its language. What is natural? What is unnatural? Certain people would have you believe the latter includes wild women, queer folk, the sexually liberated, and many other groups that don’t conform to the culture’s dominant social values. That culture, succinctly called the ‘heterosoc’ by Derek Jarman, elect themselves experts in their fight against wildness creating a political cultism enabled by right-wing fundamentalism and evangelicalism that gives the folk horror evoked by Y Bala a stinging relevance. It’s hard not to see the parallels amongst the Christian and Alt-right commentators that pile onto left wing, wild women and the Pagan cult groups who burn outsiders inside wicker structures if they’re seen as a threat to their social or moral values given their objectives are strikingly similar.

In reality, however, when faced with a woman who embodies their ideals, most end up balking at the idea of what they want thus emphasising a general dissatisfaction with their ideological goals. In Ari Aster’s contemporary folk horror Midsommar, for example, Dani is totally reliant on her boyfriend Christian. She seeks his validation, concedes when he tells her she’s overreacting, and worries that she leans on him too much by burdening him with her emotions. In many ways Dani is the ideal tamed woman in that she cares far more about Christian’s feelings than she does her own. Still, he isn’t happy. He is with her out of obligation and a fear that he might not find anyone better. To Christian and his male friends, Dani is a buzzkill. She nags, is clingy, and doesn’t ‘like’ sex which opens a classic contradiction within male chauvinism that a woman must be sexual enough to satisfy their needs, but not be too sexual. As always, their needs are paramount, in all areas, and they show no sympathy when Dani’s parents and sister die in a horrific way and, worse, she never expects them to.

On an anthropological trip to a Swedish village to witness the rituals of the Hårga, a pagan commune, Dani and Christian’s relationship falls apart. Christian has his head turned by one of the village locals, and through a love spell he is drawn into a mating ritual that Dani stumbles upon. Distraught by this, Dani is surrounded by female commune members who viscerally empathise with her, loudly crying along with her. This empowers her in her new position as the commune’s May Queen, a role she has been given since winning a traditional dance competition. Shortly after she is crowned, Dani is placed on a thrown of vines that seem to move, unsettlingly, as if breathing with her. The garnish that decorates the feast moves, too, as Dani becomes one with nature. Her crowning completes Dani’s journey into wildness, one that is signposted by her drug infused trips in which she sees grass grow from her hands or her feet become reeds. Throughout Midsommar, Dani is moving away from her position as a tamed woman and into wildness. She begins to question Christian’s motives and his character, wondering if he is a good man. The completion of her journey from tamed to wild is visualised as Dani is literally embraced by nature when she is enrobed in petals leaving only her head visible. Now she is no longer tamed, she can retaliate by burning Christian alive inside an ancient temple and watching over the scene with a smirk. Thus, she is emancipated. Or is she?

For some, Midsommar’s ending is liberating and cathartic. Yet, liberation from being tamed and moving into the wild doesn’t mean moving into goodness or righteousness. Some, like Dani or Cathy, do nasty things when they embrace their wildness. They can be manipulative and violent, cruel and cold. As such, these women aren’t the role models some contemporary feminists might wish for when looking to representations of women in film, but they are, perhaps, more valuable to the cause. Dani, for example, can be our hero and make a bad, possibly evil choice. The fact we empathise with her reasoning or find her decision understandable, if not condonable, suggests that what we’re really craving or celebrating is an escape into wildness, which is really an escape into a nuance that isn’t allowed within a society that likes things fixed. Wildness, whether good or bad, means an escape from the confines of social regulation. We are drawn to Cathy or Dani because we can see that emancipation and crave it for ourselves. Yet, they also represent our fears too. What would it mean to be unregulated? What would we do if we were free? How would we behave if we were truly wild?

‘The Wild Woman’ originally featured in the exhibition catalogue for Y Bala (2023), a collaborative exhibition by Anna Jane Houghton and Abbie Bradshaw at The Royal Standard to coincide with the Liverpool Biennial.

Leave a comment